Community life competence

Connecting local responses around the world

Connect with us

Website: the-constellation.org

Newsletter English, French Spanish

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Constellation/457271687691239

Twitter @TheConstellati1

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/constellationclcp/

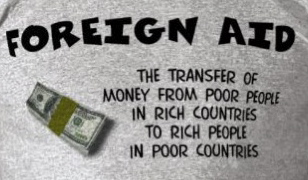

Aid, Africa, Corruption, and Colonialism: An Honest Conversation

I’m sharing an interesting discussion that’s been going on via the LinkedIn Africa NGO Network group, "Why is development aid having corruption problems in Africa generally?". Some of the key contributions on root issues follow below. Unfortunately they are important issues not heard often enough in aid effectiveness discussions. I offer this food for thought for aid workers and do-gooders alike.

***

Dr. Chris Etuka Obinwa (Researcher): The people at the grassroots in the home countries are not involved from the takeoff stage to the conclusion of the projects. Secondly, the policies designed are at variance with the home countries policies. Thirdly, lack of sustainability of most projects. These create a huge gap which those involved take undue advantage of.

Godifri Mutindi (Learning Advisor & Consultant): The agency theory shows that people naturally chase their own [interests], rather than other people’s or even the group objectives. Going back to traditional Africa, the community welfare system, which was to take care of orphans, was abused. Philanthropists take advantage of this goodwill from the public—that they are people who want to improve the marginalised's welfare and chase their own interests. History has shown that even religious movements (those who are supposed to be the greatest philanthropists) and the socialist governments are very corrupt. When there is little accountability and transparency, especially in Africa, this is a recipe for disaster.

Poverty is big business all over the world, not only in Africa. In this big business, where billions are poured by donors and bilateral partners, governments (through well-connected officials) and NGOs (including international ones) have a big party. Are these entities, who abuse and enjoy poverty-related resources, particularly interested in solving the real problem—poverty, ignorance and discrimination?

Jennifer Lentfer: The problem persists because local civil society organizations are currently the lowest common denominator of international development assistance. I think it’s time to recognize local initiatives and indigenous organizations as vital to supporting demand-driven development that can genuinely challenge power asymmetries, and unleash social change.

We continue to witness Southern organizations or “partners” being rebuilt into more professional organizations that lose their character and represent only the interests of the community that align with funding or Northern NGO guidelines. This should ultimately lead us all to ask - whose interests are really being served?

Dr. Tererai Trent (Senior Evaluation Consultant): Jennifer and Godifri you both speak to the heart of the issue. I wish such discussions could be part of the dialogue when policies are being instituted. Hey, it's time to recognize the vital role that can be played by involving local grassroots organizations. It's sad but in the name of 'expertise,' indigenous organizations have remained in the margin, and left to receive the leftovers, and yet, these local organizations hold the key to sustainability.

Godifiri, you raise a critical point—the disappearance of the community welfare system, and yet, the Northern friends speak about cultural appropriateness, empowerment, participation, collaboration and all those money-making-catch phrases. I know there is no justification for corruption. But unfortunately an unintended recipe is being created for it.

Thanks Dr. Atuka for highlighting the implications of conflicting policies. So the question for me is; those of us who would like to see change, what is it that we can do beyond airing our views?

Jennifer Lentfer: We all know that currently there is a large discrepancy between the resources that are mobilized or acquired by donors, governments and international organizations for global development, and what percentage of the money actually reaches communities and local leaders. I am working to advocate for far-reaching and responsive small grant mechanisms that will support local indigenous organizations to assist communities to become more adaptive and resilient, and building civil society in the process. People, under the direst of circumstances, can and do pull together. My hope is that the relief and development aid sector can finally recognize this.

Godifri Mutindi: We have to agree on the meaning of 'corruption' in this industry. Besides obvious cases such as embezzlement of funds and fraud, which are common in developing countries (but much more developed in the West), what about:

1. The racist and nationalist employment policies of international organisations, especially at top management level. It's almost a law that an NGO from such a country has to have the Country Rep, Finance, Operations and Project Director from the same state or at least, of pale skin. Many a time these so-called specialists have very low qualifications and are appointed through connections.

2. Very large gaps between the locals and the expatriate conditions of service, even for people with the same qualifications. One cannot stop wondering how an organisation using the US$ pays its personnel in local currency and denies them a decent living.

3. Top-down management, even for rights-based approach' organisations. Jennifer has already expounded on this. There is no engagement and consensus on issues. The expatriates and a few handpicked nationals generally agree on self-serving policies and report these externally as the developing countries' consensus.

Jennifer Lentfer: Thank you for expanding the definition of corruption in aid, Godifri. I always think it is ironic that INGOs never look to themselves as contributing to the fraud and embezzlement. Where is the self-reflection among donors about each layer of bureaucracy taking their share of the aid funding before it ever reaches the ground?

Njoroge Kabugu (Student and blogger at The Bigger Village): I do agree and would also add that we as an African people do know the solutions to our problems to begin with. Can we not form or support local and national NGOs that are run on ethical principles, and also that push for public policy that will strengthen the NGO sector? I know we have organizations that can dig wells, construct schools, provide financial services etc. which, if there were the right policies, would be used at the national level to provide those services that the international NGOs do. When a donor gives a grant in the US, they do not have one of theirs employed to follow the money. The same should follow for Africa.

On another note we in the Diaspora also need to support our NGOs in Africa. We can create an umbrella organization that can influence public policy, set ethical standards, monitor local and international aid, exposing corrupt practices by both the local and international NGOS, as well as providing funding to organizations on the ground that are up to par on how they conduct business.

Godifri Mutindi: I have heard an interesting story about African professionals. They are compared to crabs in a pool, which want to climb onto a rock, in order to get out. Each one of them wants to do it alone, thus loss of synergy. Actually, when of them starts climbing, the other ones bite the leg and pulls them back into the pool! To them, it's ok to suffer together, rather than seek a unity of purpose or support those who have the determination. I wonder if this analogy is true or to exaggerated.

But check our politics, education, football and even religion—there is an unmistaken egoistic thread running along. We easily divide ourselves into national, religious, regional, ethnic and racial blocks. (I don't want to believe someone manipulates us). It seems as if the educated African has greatly failed his continent because the exploitation and corruption (the matter under review) is not done using illiterate people. Our own graduates, whether in government or NGOs, benefit and collaborate in expropriation of poor and marginalised communities of the resources meant to uplift their lives. Please, read the late Ken-Saro Wiwa's political sattire, 'The Prisoners of Jebs".

F. O. (Monitoring & Evaluation Professional): Well, development aid corruption is just a song played and listened to in Africa in general. The cause of this is just centered around [what] I would generalize as expressed by African leaders as "dark-hearted national power interests". This is where we should start from. In Africa, it is common that leadership is characterized by selfishness, which is perpetuated by direct and indirect promotion of ethnicity. This is through provision of social, political and economic privileges to particular groups of people.

Divide and rule technique is applied to break down linkages that easily topple ruling governments. [It] is applied because they are aware of the fast moving waves of formal education across their societies? [This] style of leadership is what you find up at the top to the grassroots in Africa. These have all broken down the African traditional systems discussed by others and this has been existing for a long time. It is thus not surprising when aid is misused in such societies. Africa still needs leaders with vision like Mandela—a leader who can set an example that will later impact on the social, economic and political development of a nation.

***

When I asked Dr. Trent if she’d be willing to include her comments in this post, she went on to share the following, which leave us with some important questions to consider going forward:

Dr. Trent: I am so surprised that many of us fail to see the continual perpetuation of [a] colonial way of approaching development in Africa. This is not a blame game, but reality at its core. In most African communities people are used to see[ing] the West bringing aid. They get excited, women ululate and the men clap hands because their expectations for a better future are raised, and then everything disappears like rain. Who gains and gets empowered in this process? Outsiders' resumes and curricula vitæ are powerful and rich, and yet, 'the insiders' resumes are empty and labeled with corruption and laziness. Whose reality of development is it?

The dependency syndrome which comes with aid and the "stereotypes and assumptions of who poor people are, what they need, and how they can be helped" fails to recognize peoples' intelligence, strengths and resilience. Mechanisms for accountability are one-sided and built upon mistrust.

As aid deliverers why are we failing to confront our own stereotypes? Why do we ignore the sovereignty of these communities we say we help? Why do we bring to them frameworks and approaches that work elsewhere without questioning their validity? Should the Western epistemology, ethics and concepts be the main default lens for development in Africa? (For more information on this topic, see my post on the Genuine Evaluation blog, “Where and Why Western lenses miss the mark in Africa: The case of H...”.)

More[over], where are the local indigenous experts? Are they included in major think tanks, or is their inclusion more of a perfunctory effort in order to deflect criticism or comply with some rules? Are local experts actively included in the decision making of aid and how it should be delivered?

***

This post originally appeared at: http://www.how-matters.org/2011/04/22/aid-africa-corruption-colonia...

***

Related Posts

Trocaire: 10 things INGOs need to do

I lied…

Confessions of a Recovering Neocolonialist

Changing the system…from the ground up

Reuters: New report, model of best practice for aid world

© 2024 Created by Rituu B. Nanda.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Community life competence to add comments!

Join Community life competence